Red, White and Royal BOO: Why the Book is Better

By JT Thomas

Helloooooo College Democrats! Did you miss me?

That’s right! After my lengthy sojourn across the Pond I’ve returned to you, my beloved captive audience. For those of you who don’t know me, my name is JT and I’ll be serving as your Communications Chair for the 2023-2024 school year. For this iteration of Being Blue at PSU, we’ll be continuing with our theme from last year, bringing you a mixture of fun, whimsical pieces (which are still in some way connected to Democratic values) and more traditional articles based on important political issues.

Let’s start things off on a fun note, shall we?

Last year for our first post of October, I wrote a review of Casey McQuiston’s 2019 bestseller Red, White and Royal Blue. The novel itself is fantastic; McQuiston manages to seamlessly integrate a sensual, steamy queer romance with a compelling storyline full of real world issues. So, imagine my surprise and delight when I heard that Prime Video was working on a screen adaptation of the same story, one that was to be written and directed by a gay, Latino man.

Ignorance is bliss, I guess.

The movie in and of itself is not bad. It’s not a cinematic masterpiece either, but if you’re able to separate what you see onscreen from what you’ve read on the page (or if you’ve never read the book in the first place) it becomes a slightly predictable but otherwise palatable rom-com with a few memorable moments that hint at something more profound lurking backstage, just waiting for its cue. However, if you’re like me, the film ends up as a washed out, shallow, hollow shell of what it could have been. Changes were made and characters were left out, which leads to serious negative impacts on the overall themes of the book. What’s even more frustrating is that very few of these changes or omissions make sense, even from a time perspective. For crying out loud, the whole runtime of the film (with credits!) is only two hours and one minute. Some people might not be a fan of longer movies, but personally I would prefer a longer, accurate film rather than a short one that falls short.

But, then again, how exactly does it fall short? Let’s find out.

*As a warning, the rest of this post contains major spoilers for BOTH the film and book versions of Red, White and Royal Blue. Read on at your own risk.*

As I said above, my main content problems with the film can be divided into two categories: things that were left out and things that were changed. Let’s start with the former.

First and foremost I have to put the character June on this list. In the book, she’s Alex’s older sister, the third member of what’s known as “the White House Trio,” which is made up of her, Alex, and Nora. June is a critical part of Alex’s support system. In many ways she’s Alex’s rock; she’s fiercely supportive and protective of him, while also not being afraid to call him out on his bullshit. While Nora is the one who kinda sorta talks Alex through his sexuality crisis (something also left out of the movie, but more on that later), June is the one who really helps him come to terms with the amount of depth his relationship with Henry has gained. She’s the eye of the storm in the Claremont-Diazes’ complicated family life, and her absence turned me off to the movie within the first ten minutes.

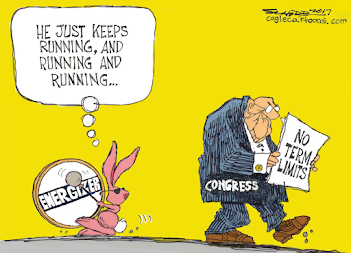

Second on the list of omissions is Senator Rafael Luna. Most of the book’s political subplot is left out of the movie, including the charismatic Independent from Colorado. Luna is a family friend to the Claremont-Diazes, as well as a confidant and role model for Alex himself. His character and choices drive Alex’s (and by extension the reader’s) exploration of what it means to be a politician, especially a politician who is neither white nor straight. Luna’s subsequent betrayal (or as Alex refers to it, “selling out”) by joining the campaign of the right-wing candidate Jeffrey Richards rocks Alex to his core, and while the situation is eventually resolved and their relationship restored, the shift still causes Alex to reevaluate the path that he’s on, with the added bonus of forcing the reader into some critical thinking. Luna is also the lens through which McQuiston examines abuses of power within certain sectors of the American political atmosphere. His story as a survivor of attempted sexual assault and his abusers subsequent blackmailing of him into silence is a powerful and deeply relevant part of the book which is left out of movie.

The third and final major character left out of the film is Princess Catherine, heiress apparent to the British throne and mother to the royal siblings, including Henry, Alex’s love interest. Catherine is mentioned several times throughout the book during discussions of the losses that Henry and his siblings have suffered, but only shows up in the flesh in the last act. She makes this appearance count, however, politically blackmailing her mother (the queen) into allowing Alex and Henry to publicly confirm their relationship after their emails are leaked. Catherine is, as Henry says, “such a spitfire;” she’s daring and a bit of a rebel herself, having met Henry’s deceased father after ditching her security at one of his shows, and marrying him despite Queen Mary forbidding her to do so. Oh, and she’s the first in-universe Princess to have a doctorate. Catherine is an integral part of the book’s discussion on grief and parenthood, as well as its exploration of minoritized groups in power.

Now comes the list of changes, of which there are many, both to content and to character. Some changes are admittedly benign and do little to either help or harm the movie’s plot or themes, like the change from Queen Mary to King James, a move which I suspect was in deference to Queen Elizabeth’s declining health (she would pass away around a month after filming wrapped). Also in this category are changes which are benign yet frankly bizarre and unnecessary, such as changing Jeffery Richards’ position from a Senator from Utah in the book to the Governor of Michigan in the movie. More prevalent, however, were changes that greatly impacted the narrative, characters, or the themes inherent to them.

Starting things off is the relationship between Alex’s parents, Ellen Claremont and Oscar Diaz. In the book, the two are divorced and often get into fights when they’re together. This helps further Alex’s struggle with his identity, which he often feels has been split in half. It makes him seek comfort from other sources: June, Nora, and eventually Henry. The pair’s complicated relationship with each other and their children also furthers the book’s discussion on parenthood and family struggles. On the other hand, in the movie the two are portrayed as a happy couple, which obviously upends the above and ruins the accompanying thematic questions.

In both versions of the story, Alex and Henry are outed to the world when the emails they’ve sent to each other are hacked and leaked online. In the book, this attack is a malicious plan concocted by members of the Republican presidential campaign to try and sabotage Ellen Claremont’s reelection. In the movie, it’s implied that the emails were obtained and released by one of Alex’s past hookups, a journalist named Miguel. While this might not have a specific thematic impact, it does cheapen the narrative by turning it into a petty, flimsy revenge plot.

Alex and Henry’s best friends both took substantial hits in the transition from the page to the big screen. In the books, Nora is a quirky, nerdy, and quite literally a genius. Like her movie counterpart, she works in statistics, though her skill is downplayed. Pez Okonjo is charismatic and good at just about anything he does. He’s also a billionaire philanthropist bundled up in a floral bomber jacket, something that is only lightly touched on in the film. These two characters are, essentially, the Ginny Weasleys of the film; in the source material they’re well-rounded, fiery, interesting characters in their own right. In the movies, not so much.

Another character who suffers this kind of treatment is Henry’s sister Princess Bea. In the book she’s the older of the pair, while in the movie she’s been demoted to younger sister status. This change might seem harmless, but it fundamentally changes the siblings’ dynamic. In the novel, Bea is full of advice and support which are grounded in real life experience, something that is only present in the film for one brief (and in my opinion unmoving) scene. Bea as a character has so much to give; in the book she’s a recovering cocaine user, an addiction she developed after her father’s passing. She’s in part a spoiled rich kid, but simultaneously a survivor who’s seen some shit. Her past experiences make her seem older than she is, and help to legitimize the advice she gives to Henry, Alex, and even her own mother. Part of what I think makes Red, White and Royal Blue a successful book is its ability to tell multiple stories through multiple different lenses that each enhance the others. Bea is a prime example of this. Her story about second chances has depth and is vitally important to tell, and it’s a shame that the filmmakers disagreed.

As if paring down the side characters wasn’t bad enough, both main characters suffered significant hits in the transition from page to screen. Almost all of their ticks and flaws have been written out in order to focus entirely on their romance, something that might be mildly entertaining but ultimately leads to flat characters. The entire first half of the pair’s relationship revolves around (at least from Alex’s point of view) stripping Henry of his fairytale facade and making him into a fully human, flesh-and-blood character, something not present in the film adaptation. Henry’s neuroses and interests (such as the gay history of England) are almost entirely absent. His expertise in English literature, as well as his skill as a writer on his own are only superficially present in the film. One of the parts of the book that resonated with me the most was Henry’s struggle to accept the fact that he is deserving of love, in spite of what other people might tell him and the impacts of grief on his life. Henry is a character with so much emotional depth, depth which the filmmakers almost entirely threw out.

Alex in the books is much more than a pretty face; like Nora he’s intensely smart, studying government at Colombia and graduating summa cum laude, not to mention landing a well-deserved job working with policy on his mom’s campaign. Even before his official hiring he’s an invaluable political asset to the President; it’s well established in the books that one of his favorite pastimes is charming elected officials into giving him all the details on bills, endorsements, et cetera. He has wit and passion to spare, as well as his fair share of anxieties and neuroses. All of this is only faintly present in the movie, if it’s present at all. The most egregious change made to Alex’s character (and quite possibly the most egregious in the movie as a whole) is that by the time Henry kisses Alex for the first time the latter has already “hooked up” with three guys. They took out his entire journey towards finding his identity and accepting himself, something that is literally the entire point of a good portion of the book.

Red, White and Royal Blue was a book with so much potential for a film or TV adaptation: the story, characters, and dialogue were all there, just waiting for someone to bring them to life. Unfortunately, what fans of the book were handed was a pale reflection of what should’ve been. Many of the heavy-hitting, emotional aspects of the book were skipped over or written in a way that lessened their impact. Likewise, many characters were either written out or pared down to make way for the romance between the two protagonists. I understand that prioritizing romance over substance has become something of a given in the rom-com biz, but to that I say this:

If writers are going to omit all the little quirks that made their characters fall in love with each other in the first place, then what’s the point?

Comments

Post a Comment