The Greatest Man in the Room: Reflections on Robert Caro's "Master of the Senate"

“Answer not a fool according to his folly, lest thou also be like unto him. Answer a fool according to his folly, lest he be wise in his own conceit.” - Proverbs 26:4-5 (KJV)

I remember first hearing of Robert Caro’s sprawling four-volume series The Years of Lyndon Johnson over half a decade ago, when a teacher held up one of the books as an example of a tome that might kill a man if you plopped it onto his head. At 3,378 pages and over 1,900,000 words, the four volumes together are nearly twice as long as Edward Gibbon’s monumental Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire–and there is a fifth and final instalment of the series on the way. Not a little intimidated by their length, I put off reading the books until, last December, I was looking forward to an uneventful winter break and decided there would be no better time to have a go at it. I went off to Pattee Library and pulled the third volume, The Master of the Senate, off the shelf.

I chose to start in medias res, rather than with the series’s first volume, because I had already had the vaguest understanding of Lyndon Johnson’s career in the Senate, and because I thought it would make for more interesting reading. The Master of the Senate begins with Johnson’s fraud-ridden election to the Senate in 1949. The book meticulously trails his ascent up the Senate Democrats’ ranks, first as a committee chairman, then whip and deputy leader, and finishing as Senate majority leader. After documenting how Johnson, to borrow an epigram from Disraeli, “climbed to the top of the greasy pole,” the book ends with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, Johnson’s coup de maître as majority leader.

The question at the heart of the narrative is this: How did a brash, low-born senator from Texas come to dominate the Senate as no man had done in a century? And, furthermore, how did Johnson, a son of the South and a thoroughgoing racist, manage to enact America’s most progressive racial legislation? The Master of the Senate takes over one thousand pages to answer these questions, and it took me no fewer than three months to reach the conclusion. True to form, Caro’s writing is dense, minute and information-laden. The dramatis personae number in the hundreds. Nevertheless, the book is an absolute triumph, a work unlike few before it and nothing since, and despite its length, not one word in it is wasted.

At its base, The Master of the Senate is the study of the life of one extraordinary man, Lyndon Johnson. Throughout his narrative, Caro paints a comprehensive portrait of Johnson’s character. The portrait is not particularly flattering. No need to put too fine a point on it–Johnson was a crass, contemptible human being, an absolute ogre to his subordinates, a social and intellectual cretin and a rapacious sexual philanderer. He was, at the same time, an incredibly cunning political operator, a man with an unrivaled talent for legislative wheeling and dealing and an astonishing ability to hatch plots and lay schemes. Helped by chance and circumstance, these skills carried Johnson straight through America’s halls of power.

Pulling back, The Master of the Senate is not only a biography of one man but the overarching story of the legislative body that that man inhabited and came to embody. Caro takes us back to the spring years of the republic, when the Founding Fathers threw down the foundations of America’s political system. The Senate, then a body of 26 appointed wise men, was created in response to an overabundance, as the Founders saw it, of democracy under the Articles of Confederation, what John Adams once colourfully referred to as “democratical, Hurricane, Inundation, Earthquake, Pestilence.” Under the newly-minted Constitution, the Senate was meant to act not only as a check against an overreaching executive, but also as a “cooling saucer” in George Washington’s words, a place where the popular tempers of the elected lower house could simmer down.

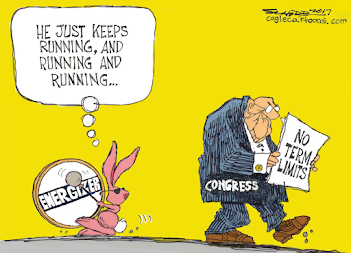

Whatever the Founders’ intentions for the Senate were, the result was a chamber that was essentially conservative, predisposed to oppose change. America’s upper house became an old boy’s club dominated by aged, land-owning patricians (as it happens, the words senate and senator ultimately derive from Latin senex, meaning “old man”). It is not surprising, then, that the Senate took a regressive view on slavery and rights for Black Americans. Ante-bellum Southern senators, America’s optimates, saw in the Senate a mechanism of safeguarding their minority rule over the South, keeping slavery alive in a country that, for the most part, had turned against the “peculiar institution.”

The Senate’s disreputable legacy of opposition to Black rights carried over into Reconstruction and beyond, when the filibuster was used to crush civil rights legislation originating from the House. Eventually, the Senate became known as the place where progressive ideas went to die, a corrupt and sclerotic institution unworthy of the democratic age.

This was the Senate that Lyndon Johnson was elected into. And it proved a staging ground for him to exercise and hone his political skills.

A consummate egoist whose remarkable quality was an insatiable lust for power and fame, Johnson never shied from employing his talents in the service of evil. One of his earliest masterstrokes as a senator was a successful character assassination of Leland Olds, a devoted New Deal-era civil servant who was up for reappointment as Federal Power Commissioner. Olds’s progressive administrative program threatened the Texas oilmen who stuffed Johnson’s pockets. Over a hundred pages, Caro describes how Johnson, in the guise of a disinterested committee chairman, successfully sowed rumors that Olds was a communist and disloyal to the United States. Olds was denied reappointment and died poor and disgraced, thanks to Lyndon Johnson.

Other times, however, Johnson was able to put his skills to more positive effect. Better than most politicians of the South, he read (to borrow another British prime minister’s words) the winds of change blowing through the United States, winds favorable to civil rights for African Americans. Johnson, who had been as consistent as any other Southern senator in opposing anti-lynching legislation, gradually more sensitive to the condition of his Black constituents. Caro writes on page 889, “[Johnson] felt the hurt, and he felt for the people who had been hurt–felt the injustice and humiliation that had been visited upon them.” To what extent Johnson’s volte-face on civil rights represents a genuine change of heart or a calibrated political move is worthy of debate. In any case, Johnson went from being the devoted opponent of civil rights legislation to leading efforts to pass civil rights legislation in a conservative Senate that had for decades stood against the slightest suggestion of Black rights.

The culmination of Johnson’s work on civil rights as a senator, the Civil Rights Act of 1957, was the first such piece of legislation to receive the Senate’s imprimatur in over half a century. As a piece of civil rights legislation, the 1957 bill is admittedly pathetic and does not go nearly far enough. But it is a testament to Johnson’s political genius that he was able to steer the bill’s passage in a legislative body where civil rights had encountered unbeatable resistance and morass. What’s more, the 1957 law prefigures its more robust successors, the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965, whose passage Johnson orchestrated as president. Those bills are the stuff of Caro’s subsequent volume, The Passage of Power.

What mattered most about the 1957 Civil Rights Act was not the language of the law itself, inadequate as it was. Rather, the bill reflected the tide of progressive change that, in the next decade, would culminate in an out-and-out social revolution. Caro quotes Johnson: “For the first time in memory, this issue [civil rights] has been lifted from the field of partisan politics. It has been considered in terms of human beings and the effect of our laws upon them.” That, perhaps, is the ultimate legacy of the Master of the Senate.

What should we make of Lyndon Johnson? I am conflicted. As a Democratic politician, he is one of the most effective in American history. Johnson single-handedly revitalized the office of whip and majority leader in the Senate, previously referred to as the “nothing job.” As president, he presided over arguably the most progressive programs in American history–namely civil rights and the Great Society, which lifted millions of Black Americans out of poverty. All the same, Johnson represents a corrupt, pernicious and reactionary element of American politics. The institution that he so successfully led, the Senate, remains an essentially conservative and undemocratic institution. The filibuster, once used to crush anti-lynching legislation, is still employed to great effect and Senators remain a predominantly old, predominantly white and entirely unrepresentative slice of the American population. It is fair to say, then, that Lyndon Johnson manipulated the system to achieve some good ends rather than change the system itself.

I am not, however, conflicted in my thoughts on Caro’s biography. The Master of the Senate is an exceptional work, a permanent addition to the American academic canon, and one of those texts that anyone who wants to understand American politics should read. Normally, I would say that it is useless trying to tell the books will survive into posterity from those that end up gathering dust, but I am keen to make an exception here. I have no doubt that Robert Caro and his work will be remembered by historians of the future in much the same way historians today remember the contributions of Tacitus and Edward Gibbon.

Comments

Post a Comment